A Convergence of Science & Real Magic – New Dawn : The World's Most Unusual Magazine

by Dean Radin

The word “real” in the title distinguishes the type of magic we’re discussing. This is not about the fictional magic of Harry Potter or the fake magic of Harry Houdini. This is about real magic, which falls into three main categories: divination, or perception of events distant in space or time; force of will, or mental influence of the physical world; and theurgy, or interactions with nonphysical entities.

In my book Real Magic (Harmony, 2018), I describe how these traditional, esoteric forms of magic (occultists use the term “magick”) have been scientifically studied for over a century, and why the accumulated evidence in favour of real magic is now overwhelmingly positive. This assertion might be surprising given that college textbooks teach us that magic is merely an ancient superstitious belief. But textbooks are regularly revised and updated as science marches on, and at the leading edge of science today we’re finding that some of the ancient ideas about magic are actually correct. Science and magic appear to be converging.

How do we know this?

One strong indication appeared in May 2018. The American Psychological Association (APA) is the principal organisation for academic and clinical psychologists, with nearly 120,000 members worldwide. Its flagship journal is the august American Psychologist. In the May 2018 issue, a lead article was entitled, “The Experimental Evidence for Parapsychological Phenomena: A Review.” The author was Etzel Cardeña, a psychology professor at Lund University in Sweden. After analysing ten classes of experiments exploring psychic effects (“psi” for short), the article’s conclusion was unequivocal: “The evidence for psi is comparable to that for established phenomena in psychology and other disciplines.” That this article appeared in the conservative voice of academic psychology cannot be overstated.

There are many other signs. For example, University of California statistics professor Jessica Utts was President of the American Statistical Association (ASA) in 2016. The ASA is the world’s largest organisation of academic and professional statisticians. In her Presidential Address in 2016, Utts mentioned that one area she had studied in detail for the US government was parapsychology. She said: “The data in support of precognition and possibly other related phenomena are quite strong statistically and would be widely accepted if they pertained to something more mundane.”

These are just two examples, but there is an increasing number of scientists who are willing to say to their peers, in public, that based on evaluation of the experimental evidence, psi exists. This is hardly news to the majority of the general public who already believe this, but among many scientists the mere possibility that psi might be real has been such a contentious issue that few were willing to express such positive opinions in public. The reason for the ongoing debate has had very little to do with the evidence and very much to do with the scientific worldview – that collection of ideas that form how science understands reality and our place in it.

The debate over psi has persisted for hundreds of years because generations of students have been taught that psi violates one or more unspecified laws of physics, and so any claims about it, either experiential or experimental, must be mistaken. This belief has forced psi out of the academic mainstream, and its marginal status has had important consequences. As the late Irvin Child, former chair of the psychology department at Yale University, wrote in 1985 in American Psychologist:

Books by psychologists purporting to offer critical reviews of research in parapsychology do not use the scientific standards of discourse prevalent in psychology. Experiments… on possible extrasensory perception (ESP) in dreams… have received little or no mention in some reviews to which they are clearly pertinent. In others, they have been so severely distorted as to give an entirely erroneous impression of how they were conducted.

We see these distortions starkly reflected in the contemptuous way that Wikipedia articles describe topics in parapsychology. This is a pity, not only because psi phenomena are extremely common human experiences, but because the state of the scientific evidence is so strong. Still, many journalists within the “serious” media continue to portray such experiences at best as spooky or silly, and at worst as a sign of mental illness. Despite the evidence, it’s not surprising that this topic has become an entrenched taboo.

I explored where this taboo came from, and why it persists, in Real Magic. I surveyed the history of the esoteric traditions, the classes of magical practices, magic’s relationship to psi, what scientific tests tell us about magic, and why leading-edge scientific ideas are suggesting a science/magic convergence. The bottom line was as follows: When you survey 10,000 years of esoteric history, ranging from shamanism through Neoplatonism, Hermeticism, the Kabbalah, Gnosticism, the Rosicrucians, the Free Masons, and so on, you find that they are all based on a single perennial wisdom that can be summarised in three words: Consciousness is fundamental.

By consciousness, I mean a primordial, universal awareness, a perplexing type of “substance” that’s woven into the fabric of reality. From this esoteric worldview, scientific concepts like space, time, energy, and matter are said to emerge out of a universal consciousness. It also means that our personal sense of awareness, our self-consciousness, is composed of the same stuff. The esoteric traditions tell us that ultimately you are the universe. That is, universal awareness is the source of everything, including our bodies, brains, minds, and that spark of awareness within you that you call “me.” This is the source of the affirmation mantra “you create your own reality,” and it is meant in a literal sense. The esoteric worldview makes it far easier to understand psi experiences like telepathy and clairvoyance because the idea that awareness spans all space and time, and that it can manifest the physical world, is simply a consequence of the nature of consciousness itself.

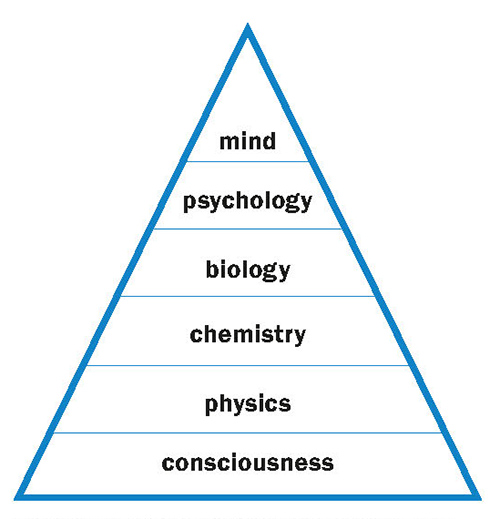

Dean Radin proposes a more comprehensive knowledge hierarchy which places Consciousness (C) at the bottom to indicate where the physical world emerges from. At the top of the pyramid is Mind, meaning the brain’s machinery involved in information processing, cognition and perception. From this perspective, he says, “we enjoy conscious awareness not because the brain generates it, but because (C) permeates every layer of the physical world, just like electrons permeate every later ‘above’ the discipline of physics. Based on his hierarchy, which maintains everything currently known in science… magic is no longer an impossible anomaly.”

What does this have to do with real magic?

Real magic is the pragmatic application of the esoteric worldview, just like today’s technologies are the application of the scientific worldview. That is, if consciousness is indeed as fundamental as the esoteric traditions claim, then magic must be genuine because awareness is primary over the physical world. Thus, we have the capacity to transcend the limits of space and time, and we can determine (to a small extent) how the physical world emerges. Further, human embodiment can now be seen as just one way, among a potentially infinite number of other ways, that consciousness can manifest into a physical being.

Why aren’t there university-based departments of magic? Why can’t we earn an accredited advanced degree in magical practice? The usual answer is that the esoteric worldview is so radically different from today’s scientific worldview that it cannot possibly be true. But that’s only because the scientific worldview as portrayed in the typical college textbook is five to ten years out of date. The leading edge today in science, represented by articles and books written by mainstream thought-leaders in physics, mathematics, and the neurosciences, is proposing that reality is literally made out of information. That is, the emerging scientific worldview tells us that reality is not composed of matter or energy, but rather of something far stranger, more abstract, and much closer to the esoteric worldview than the materialistic perspective that’s commonly associated with science.

Full story at site

by Dean Radin

The word “real” in the title distinguishes the type of magic we’re discussing. This is not about the fictional magic of Harry Potter or the fake magic of Harry Houdini. This is about real magic, which falls into three main categories: divination, or perception of events distant in space or time; force of will, or mental influence of the physical world; and theurgy, or interactions with nonphysical entities.

In my book Real Magic (Harmony, 2018), I describe how these traditional, esoteric forms of magic (occultists use the term “magick”) have been scientifically studied for over a century, and why the accumulated evidence in favour of real magic is now overwhelmingly positive. This assertion might be surprising given that college textbooks teach us that magic is merely an ancient superstitious belief. But textbooks are regularly revised and updated as science marches on, and at the leading edge of science today we’re finding that some of the ancient ideas about magic are actually correct. Science and magic appear to be converging.

How do we know this?

One strong indication appeared in May 2018. The American Psychological Association (APA) is the principal organisation for academic and clinical psychologists, with nearly 120,000 members worldwide. Its flagship journal is the august American Psychologist. In the May 2018 issue, a lead article was entitled, “The Experimental Evidence for Parapsychological Phenomena: A Review.” The author was Etzel Cardeña, a psychology professor at Lund University in Sweden. After analysing ten classes of experiments exploring psychic effects (“psi” for short), the article’s conclusion was unequivocal: “The evidence for psi is comparable to that for established phenomena in psychology and other disciplines.” That this article appeared in the conservative voice of academic psychology cannot be overstated.

There are many other signs. For example, University of California statistics professor Jessica Utts was President of the American Statistical Association (ASA) in 2016. The ASA is the world’s largest organisation of academic and professional statisticians. In her Presidential Address in 2016, Utts mentioned that one area she had studied in detail for the US government was parapsychology. She said: “The data in support of precognition and possibly other related phenomena are quite strong statistically and would be widely accepted if they pertained to something more mundane.”

These are just two examples, but there is an increasing number of scientists who are willing to say to their peers, in public, that based on evaluation of the experimental evidence, psi exists. This is hardly news to the majority of the general public who already believe this, but among many scientists the mere possibility that psi might be real has been such a contentious issue that few were willing to express such positive opinions in public. The reason for the ongoing debate has had very little to do with the evidence and very much to do with the scientific worldview – that collection of ideas that form how science understands reality and our place in it.

The debate over psi has persisted for hundreds of years because generations of students have been taught that psi violates one or more unspecified laws of physics, and so any claims about it, either experiential or experimental, must be mistaken. This belief has forced psi out of the academic mainstream, and its marginal status has had important consequences. As the late Irvin Child, former chair of the psychology department at Yale University, wrote in 1985 in American Psychologist:

Books by psychologists purporting to offer critical reviews of research in parapsychology do not use the scientific standards of discourse prevalent in psychology. Experiments… on possible extrasensory perception (ESP) in dreams… have received little or no mention in some reviews to which they are clearly pertinent. In others, they have been so severely distorted as to give an entirely erroneous impression of how they were conducted.

We see these distortions starkly reflected in the contemptuous way that Wikipedia articles describe topics in parapsychology. This is a pity, not only because psi phenomena are extremely common human experiences, but because the state of the scientific evidence is so strong. Still, many journalists within the “serious” media continue to portray such experiences at best as spooky or silly, and at worst as a sign of mental illness. Despite the evidence, it’s not surprising that this topic has become an entrenched taboo.

I explored where this taboo came from, and why it persists, in Real Magic. I surveyed the history of the esoteric traditions, the classes of magical practices, magic’s relationship to psi, what scientific tests tell us about magic, and why leading-edge scientific ideas are suggesting a science/magic convergence. The bottom line was as follows: When you survey 10,000 years of esoteric history, ranging from shamanism through Neoplatonism, Hermeticism, the Kabbalah, Gnosticism, the Rosicrucians, the Free Masons, and so on, you find that they are all based on a single perennial wisdom that can be summarised in three words: Consciousness is fundamental.

By consciousness, I mean a primordial, universal awareness, a perplexing type of “substance” that’s woven into the fabric of reality. From this esoteric worldview, scientific concepts like space, time, energy, and matter are said to emerge out of a universal consciousness. It also means that our personal sense of awareness, our self-consciousness, is composed of the same stuff. The esoteric traditions tell us that ultimately you are the universe. That is, universal awareness is the source of everything, including our bodies, brains, minds, and that spark of awareness within you that you call “me.” This is the source of the affirmation mantra “you create your own reality,” and it is meant in a literal sense. The esoteric worldview makes it far easier to understand psi experiences like telepathy and clairvoyance because the idea that awareness spans all space and time, and that it can manifest the physical world, is simply a consequence of the nature of consciousness itself.

Dean Radin proposes a more comprehensive knowledge hierarchy which places Consciousness (C) at the bottom to indicate where the physical world emerges from. At the top of the pyramid is Mind, meaning the brain’s machinery involved in information processing, cognition and perception. From this perspective, he says, “we enjoy conscious awareness not because the brain generates it, but because (C) permeates every layer of the physical world, just like electrons permeate every later ‘above’ the discipline of physics. Based on his hierarchy, which maintains everything currently known in science… magic is no longer an impossible anomaly.”

What does this have to do with real magic?

Real magic is the pragmatic application of the esoteric worldview, just like today’s technologies are the application of the scientific worldview. That is, if consciousness is indeed as fundamental as the esoteric traditions claim, then magic must be genuine because awareness is primary over the physical world. Thus, we have the capacity to transcend the limits of space and time, and we can determine (to a small extent) how the physical world emerges. Further, human embodiment can now be seen as just one way, among a potentially infinite number of other ways, that consciousness can manifest into a physical being.

Why aren’t there university-based departments of magic? Why can’t we earn an accredited advanced degree in magical practice? The usual answer is that the esoteric worldview is so radically different from today’s scientific worldview that it cannot possibly be true. But that’s only because the scientific worldview as portrayed in the typical college textbook is five to ten years out of date. The leading edge today in science, represented by articles and books written by mainstream thought-leaders in physics, mathematics, and the neurosciences, is proposing that reality is literally made out of information. That is, the emerging scientific worldview tells us that reality is not composed of matter or energy, but rather of something far stranger, more abstract, and much closer to the esoteric worldview than the materialistic perspective that’s commonly associated with science.

Full story at site